/PAlogo_v2.gif)

/PAlogo_v2.gif) |

|

Post Reply

|

Page 123> |

| Author | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

DDPascalDD

Forum Senior Member

Joined: August 06 2015 Location: The Netherlands Status: Offline Points: 856 |

Topic: Composing microtonal Topic: Composing microtonalPosted: January 30 2017 at 08:26 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I have been able to experiment with two keyboards a bit, with one of the two having the pitch wheel at a fixed point somewhere between two semi-tones using adhesive tape. I like how a sudden change in pitch (microtonally) can have a big effect, sometimes very "relaxing". Here's a short demo with a Prokofiev piece (and a short improv intro): https://soundcloud.com/pascal-dool/prokofiev-microtonal/s-Z8lH4

(Please excuse me, the keyboards don't play very well so I made a few errors and some notes are left out) And an edited version of a part of The Sun Ate (from my latest album): https://soundcloud.com/pascal-dool/the-sun-ate-mcrtnl/s-71zh9

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Atavachron

Special Collaborator

Honorary Collaborator Joined: September 30 2006 Location: Pearland Status: Offline Points: 65867 |

Posted: January 15 2017 at 17:13 Posted: January 15 2017 at 17:13 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Very cool. The video should be watched to fully grasp how it works. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Too often we enjoy the comfort of opinion without the discomfort of thought." -- John F. Kennedy

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Terrapin Station

Forum Senior Member

Joined: July 23 2016 Location: NYC Status: Offline Points: 383 |

Posted: January 15 2017 at 10:39 Posted: January 15 2017 at 10:39 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

It's not inexact or random, but it's also not a science or even literally a set of rules. It's a combination of (1) a set of analysis tools--so that you have a convenient way to conceptualize and talk about the possibilities of musical materials, and (2) a study of common practices relative to historical and particular cultural milieus. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Replayer

Forum Senior Member

Joined: November 04 2013 Location: United States Status: Offline Points: 356 |

Posted: January 15 2017 at 09:12 Posted: January 15 2017 at 09:12 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

As someone interested by math and physics and as a pseudo-musician, I find this topic thoroughly interesting and entertaining. In particular, thank you, Dean, for taking the time to explain the mathematical relationships of the pentatonic and chromatic scales.

I know I took this quote out of context, but the apparent circular definition made me chuckle.

Can I go ahead and use this response whenever someone tells me that I'm wrong?  Joking aside, I agree that it is very helpful to see where the other side is coming from in disagreements. Joking aside, I agree that it is very helpful to see where the other side is coming from in disagreements. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dean

Special Collaborator

Retired Admin and Amateur Layabout Joined: May 13 2007 Location: Europe Status: Offline Points: 37575 |

Posted: January 15 2017 at 04:12 Posted: January 15 2017 at 04:12 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Okay, I'm not so stupid as to fly against consensus and convention so I concede that my use of harmony is based wholly upon the strict mathematical meaning of the term than the laxer and purely musical meaning (which is actually closer to the colloquial meaning of the word as you all have described it). I have stressed this a number of times in all my posts in an attempt to avoid this confusion. If I further limit "any pitch" to actually mean "any pitch that is one of the 12 notes in the octave" (as opposed to the infinite number of pitches [frequencies] from 440Hz to 880Hz that are not), then each pitch [note] in the 12-note chromatic scale has a harmonic relationship to at least 5 other pitches [notes] that are also in that scale. And I'm happy with that. If I adopt the convention that harmony is any two frequencies played together then obviously the maths is meaningless. Even if I then constrain that to harmony being any two notes played together irrespective of their harmonic relationship then I further concede that the determination of what is consonant and dissonant is wholly subjective (again, irrespective of the harmonic relationship between them). And I'm fine with that since whatever "works" will inevitably work, but then it all reduced down to "whatever sounds good to you" and I don't believe that Music Theory (and thus the physics of sound) is that inexact or random. We would not have arrived at the word "harmony" if harmonics were not part of the equation. However,

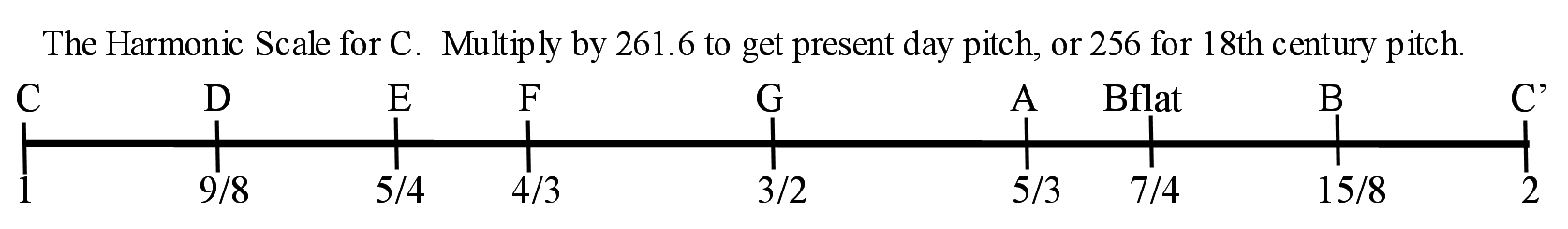

Well since all the notes on the musical scale are harmonically related by simple virtue of the interval between notes being a twelfth power of two then the relationship between any two of them will be harmonic to some extent. The relationships of 4ths and 7ths are not dissimilar in that they are both harmonics of C, so the ratio of the 4th is 4:3 and the 7th (B in the C-major scale) is 15:8 (15th harmonic), as opposed to the harmonic 7th of 7:4 (which is a 7th harmonic), which is Bb in the following diagram:  The twelve pitches on the chromatic scale are not random and they were not arrived at by accident. When music was developed back in prehistory it did not start out as a 12 note chromatic scale. There simply was no practical reason to say, "let's divide an octave into half-step intervals and see what we can do with it"... not withstanding for there to be a half-step interval means that prior to that there was only a whole-step interval which would result in a 6-note chromatic scale. The concept of steps and half-steps is an after the event 'invention'.

The earliest known scales were pentatonic - all note intervals were consonant so did not include the 4th and 7th. Early instruments with fixed tuning, such as flutes and whistles, could only play those five notes so we could say that only those 5 notes existed in the music world at that time. When those scales were transposed extra notes were needed to maintain that consonance, for example starting with a major pentatonic interval pattern: shift it by one note and the two more notes are needed giving a total of 7 to choose from (one of which is now the 7th); shifting it one more note uses one of the two new notes but two more are needed giving us a bag of 9 notes; shifting it once more uses 4 of the original 5 plus 1 of the 4 new notes and finally shifting it 4th time uses only 1 of the original 5 but all four of the new ones. But now there are 4 new notes to start that pentatonic pattern from so when the pentatonic pattern is transposed onto each of those 4 new root notes 3 more new notes are needed raising the total from 9 to 12 (which finally adds the elusive 4th to our bag). The same pentatonic pattern played starting from these three new notes all use notes from the bag of 12 so no further notes were required to play a major pentatonic from any starting note:

I illustrated this using a major pentatonic but I could have used any of the other pentatonic scales and derived these 12-notes by transposing their interval pattern sequence by one note each time. Now because each note in a pentatonic scale is harmonically consonant then each of the 12 notes from this derived bag of 12 notes will have at least 4 other notes that are consonant with it, but it was noticed that some of the remaining notes were almost consonant while others were not, so when these nearly consonant notes were incorporated into the original 5 then interesting things could happen, which resulted in the plethora of 7-note scales (but as I said earlier - only 14 of these are of practical use and only a few of those are in common use, and there is a good reason for that that is entirely down to harmony).

see above. (I agree btw but that is covered by the maths ["rules"] I have been using.) Edited by Dean - January 15 2017 at 07:31 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

What?

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

guilhermeafonso

Forum Newbie

Joined: January 12 2017 Location: Brazil Status: Offline Points: 12 |

Posted: January 14 2017 at 21:05 Posted: January 14 2017 at 21:05 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

When it comes to music theory, consonance has absolutely nothing to do with harmony... Your train of thought, Dean, is closer to what Rameau would say of it and it is true only to a time and place. If Rameau listened to Brahms, I'm sure he'd be quite dubious of the latter's prowess in harmony. Terrapin Station is quite right when he says that harmony is the simultaneous playing of any two pitches and also when he states that what determines harmonicity are cultural factors. As the times passed from medieval music onwards, more and more intervals were accepted as consonances, therefore harmony itself became more and more complex, gradually allowing a larger array of determined intervals - and this only became true due to sociocultural aspects of each moment in music history.

What you deem harmony, to use your major triad as an example, only emcompass the intervals found in the harmonic series and their interrelationships. What about the 4th and the 7th? The 4th was always a dissonance during modal times (yep, people from those times listened to it and thought of it as inharmonious - medieval theorists were even more restrictive, since they also thought this of the third and sixth), as much as the 7th. These same intervals are extremely important in any other harmonic system since tonality showed up, not to mention other changes. Finally, if we were to play by your rules, we'd only say there's harmony when there's tonality... And that's just not true |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Amused, but real in thought... We fled from the sea, whole..."

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Eviltwin

Forum Groupie

Joined: January 14 2017 Location: Brazil Status: Offline Points: 42 |

Posted: January 14 2017 at 17:50 Posted: January 14 2017 at 17:50 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pythagoras wants a word with you, actually so does Harry Partch

The 12 note system we have, organised traditionally as a 7 note diatonic scale is not an objective truth sorry to say

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Eviltwin

Forum Groupie

Joined: January 14 2017 Location: Brazil Status: Offline Points: 42 |

Posted: January 14 2017 at 17:41 Posted: January 14 2017 at 17:41 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Or maybe consonance is relative?

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Terrapin Station

Forum Senior Member

Joined: July 23 2016 Location: NYC Status: Offline Points: 383 |

Posted: January 14 2017 at 17:39 Posted: January 14 2017 at 17:39 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dean, so first off, you're trying to graft a colloquial sense of "harmony" onto music theory as if it's music theory.

In music theory, harmony refers to simultaneous pitches. It's not limited to consonance, any simultaneous pitches produce harmony, and consonance is relative. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dean

Special Collaborator

Retired Admin and Amateur Layabout Joined: May 13 2007 Location: Europe Status: Offline Points: 37575 |

Posted: January 14 2017 at 17:14 Posted: January 14 2017 at 17:14 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Because consonance is a harmonic relationship and dissonance is not. Pleasant/unpleasant, "restful"/tense, "smooth"/clashing etc. are not musical terms, they are merely adjectives that can be used to describe consonance or dissonance.

An unpleasant harmony would be an oxymoron. Harmony is not inharmonious sounds.

We don't. Pascal (the OP) asked if there was a general theory about this so I took it back to first principles to show that harmony has a mathematical relationship. I could have just said glibly "whatever sounds pleasant to you" but that fails to answer his specific question. This mathematical relationship exists - whether you choose to use it or ignore it matters not. I am a musician who is also an engineer with a love of music, maths and physics. The mathematics and physics of sound fascinate and amuse me so I love to discuss the subject. If they do not interest you then ignore them (and me).

From your perspective I am, but from mine I am not. If you think that dissonance is harmony then I cannot agree with that, dissonance is inharmonic, consonance is harmonic. Harmony is when there is a balance between consonance and dissonance and the dissonance has been resolved. I am referring specifically to harmony as the harmonic relationship between to related pitches. Harmonics therefore are not "any pitches" but are pitches that are related harmonically.

hardy har har. Read what I wrote again (not your own misquote of it), there is no tautology in what I posted.

Oh well, here's some maths anyway.

Okay so let's start at C, which is 65.4Hz. Three times C is 196.2Hz so half that is 98.1Hz, which corresponds to the frequency of a G to within 2 cents. So the frequency ratio between C and G is 3:2 and G is C raised by a perfect fifth. Even without knowing the mathematics behind it, every musician knows that the interval from C to G is a perfect fifth. When we multiply a frequency by a whole number we get its harmonic, so 2 x C is the second harmonic of C (which is C an octave higher) and 4 x C is the 4th harmonic of C (which again is C but now two octaves higher), and again 8 x C is the 8th harmonic of C (which is now C three octaves higher). However, 3 x C which is the third harmonic of C is not a C. As the previous paragraph shows, 3/2 x C is a G so 3 x C is also a G but an octave higher. Therefore the third harmonic of C is a G. So the perfect fifth is also the third harmonic of the root note. Now the really cool thing is when you play two notes together the two pitches interact and modulate each other so we perceive beat-notes, from the trigonometric identities we can prove that these beat notes are (b-a)/2 and (b+2)/2. So if the two frequencies differ by 2 Hz then we will hear a (b-a)/2 = 1Hz beat and using this low-frequency beat we can tell with extreme accuracy when one string on a guitar is out of tune. However, the (b+a)/2 beat-frequency will be the average of those two pitches and reside between them so is in the same octave (assuming that the two notes are also in the same octave). If we play C and G together then the (b+a)/2 note is (1+3/2)/2, which equates to 5/4 of C. A ratio of 5:4 is a major third, which as every musician knows is an E. Also, we now know that 5 x C gives us the 5th harmonic of C, so E is the major 3rd and the 5th harmonic of C. We played two harmonically related pitches and heard a third pitch that was also harmonically related to the root note. We played the root and the 3rd harmonic and arrived at the 5th harmonic. I hope I don't need to tell musicians here what the other relationship of C, E and G is...  None of this is coincidental.

That doesn't surprise me much, a more than a few people cannot follow what I'm talking about quite a lot of the time.

But it won't be a 3rd harmonic. Only a 3:2 relationship results in a 3rd harmonic - harmonics only result if the first number is a whole number and the second is a power of 2. Two pitches with a 7.5:3 relationship will not be harmonic so will sound dissonant.

I mean that it is not coincidental that every culture in the world devised a musical scale that approximates to a pentatonic and a pentatonic scale has been discovered in a 40,000 year old instrument which means that it is more than just subjective and it certainly isn't a matter of cultural immersion and familiarity. This is fundamentally important because the pentatonic scale has no dissonant intervals which means that consonance is universal regardless of culture or familiarity. Edited by Dean - January 14 2017 at 17:19 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

What?

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Terrapin Station

Forum Senior Member

Joined: July 23 2016 Location: NYC Status: Offline Points: 383 |

Posted: January 14 2017 at 08:48 Posted: January 14 2017 at 08:48 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Replayer, I'll check that out, but what I want is something where I can take a (musical) keyboard, and simply say, "I want 'C1' (that particular white key in other words) to be 32 Hz, and 'C#1' (that particular black key) to be 33Hz, and D1 to be 34.5 Hz" and so on.

I should be able to just call up a parameter--just call it "tuning" or whatever--on a synth/workstation/etc. that lets me specify the pitch in Hz for each key on the keyboard. It seems like that should be an easy thing to do from a technical standpoint. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Terrapin Station

Forum Senior Member

Joined: July 23 2016 Location: NYC Status: Offline Points: 383 |

Posted: January 14 2017 at 08:39 Posted: January 14 2017 at 08:39 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

So then what does that have to do with consonance and dissonance where we're referring to whether a harmony is pleasant/unpleasant, "restful"/tense, "smooth"/clashing etc. to a listener? Isn't whether harmony is pleasant/unpleasant, "restful"/tense etc. what we're concerned with as musicians, composers and arrangers? Why would we have any concern for something defined purely mathematically?

If the relationship between two pitches isn't the relationship that we define as a perfect fifth, then it wouldn't be a perfect fifth. That much is certainly correct, as again it's a tautology. Why it would matter that we don't have a perfect fifth in a given instance, who knows?

No idea what you're talking about there. If the frequency relationship isn't what we've defined as a perfect fifth, that doesn't imply that the frequency relationship is going to never be the same. It can consistently be whatever other frequency relationship we've devised.

What does "they work" refer to there? They work with respect to doing what? Being consonant? Re pleasant/unpleasant, restful/tense, etc. it's subjective whether any pitch combination merits any of those descriptions. Edited by Terrapin Station - January 14 2017 at 08:41 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Replayer

Forum Senior Member

Joined: November 04 2013 Location: United States Status: Offline Points: 356 |

Posted: January 13 2017 at 13:57 Posted: January 13 2017 at 13:57 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Your comment reminded me of a MIDI interface called the The Samchillian Tip Tip Tip Cheeepeeeee (silly name, I know) that I read about probably a dozen years ago. It was developed by Leon Gruenbaum, a musician with a degree in mathematics, and is usable with a regular computer keyboard, though he uses a customized ergonomic Kinesis keyboard as his controller. The Samchillian is based on intervals rather than pitches, so pressing one key repeatedly will increment the pitch by one step, while another key will decrement it by steps, for example. From Leon's website: "Here's how it works: a user first selects a scale and a key (e.g. F# pentatonic), and then every key that is subsequently pressed will move the user up and down a certain amount within the selected set of notes, depending on the number of positive or negative number of steps assigned to that key. Also the user is able to select from a number of scales, including microtonal scales and key signatures. A pattern, or "harmonic contour", once learned, can then be played in any key or scale without needing to relearn fingering". The Samchillian is available for $25 by contacting Leon Gruenbaum from his website, where there are few extra videos of the Samchillian in action. I remember there being a free version for non-commercial use, but can't find it anymore. This article written by Leon includes a diagram of the keys' functions. This is a demo video from 2002. Leon discusses microtonal scales between 4:24 and 5:48. Edited by Replayer - January 13 2017 at 14:24 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dean

Special Collaborator

Retired Admin and Amateur Layabout Joined: May 13 2007 Location: Europe Status: Offline Points: 37575 |

Posted: January 13 2017 at 10:47 Posted: January 13 2017 at 10:47 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Well no. Emphatically no in fact. The physics (and hence mathematics) of harmony and harmonics is universal and applies to more than just music. Two dissonant pitches will always be dissonant irrespective of who hears them and so it is with consonant pitches, so they can never be subjective/relative. This has nothing to do with acclimatisation, familiarity, conditioning or taste - it is a fundamental property of the physics of sound. Music uses a finite number of different pitches and they are mathematically related to each other so two notes that sound at the same time will have some mathematical relationship that is also related to the two original notes - if that relationship is also a note that is on the same musical scale then it is harmonious, if it is not then it is not harmonious. If this relationship didn't exist and a note could be any pitch then this simply would not work and the idea of harmony would be meaningless, so (for example) a perfect fifth would be neither perfect nor a fifth, moreover it would never be the same note each and every time it is played. These fixed harmonious notes exist because they work each and every time they are used in every music system in the world and it has been that way for at least 40,000 years so culture and acclimatisation is irrelevant.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

What?

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Terrapin Station

Forum Senior Member

Joined: July 23 2016 Location: NYC Status: Offline Points: 383 |

Posted: January 13 2017 at 09:57 Posted: January 13 2017 at 09:57 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

I don't agree with this post (not just the part I quoted) at all. Harmony obtains simply when two or more pitches are sounding at the same time. It can be any pitches. Whether a harmony is consonant or dissonant is always going to be subjective/relative to an individual, where largely it's a matter of both taste and acclimation. (With the latter, you can push yourself to hearing what you previously would have said were dissonances as consonances instead--you just need to gradually acclimate yourself to more outside harmonies. One could probably influence oneself a bit in the other direction, too, although that might be harder and I don't know if many folks are motivated to do it.) Also, "rules" in this context are just the conventions of particular historical periods and cultural milieus. Edited by Terrapin Station - January 13 2017 at 10:03 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Terrapin Station

Forum Senior Member

Joined: July 23 2016 Location: NYC Status: Offline Points: 383 |

Posted: January 13 2017 at 09:40 Posted: January 13 2017 at 09:40 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

What's a nice versus not a nice harmony is always going to be subjective. That's the case regardless of the tuning system you use. What you have to do is set up a microtonal scale that you can play on a keyboard, say--not easy, unfortunately, with the way most keyboards and software are set up, but it's possible. Anyway, you'd have to simply set up a microtonal scale on a keyboard and start experimenting with different chords, different voicings, etc. Some scales, some note combinations might sound beautiful to you. Some won't. And that's going to vary a lot depending on how acclimated you already are to more outside harmonies and how conservative your harmonic taste is. If nothing in a particular tuning is working for you, try a different tuning. I always wished that it would be standard on keyboards to (a) simply define equidistant scales--so, say if you wanted every pitch to be 33 cents apart, you should be able to just quickly set that globally, and (b) be able to define a particular pitch in cents for every key on the keyboard. You should also be able to easily define something like a 33 cents - 43 cents - 33 cents - 43 cents pattern that would be repeated globally. Unfortunately, there's not much call for that sort of thing, so keyboard manufacturers don't bother with it. I should learn programming a bit, then I could just do this sort of thing via computer. Edited by Terrapin Station - January 13 2017 at 09:41 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dean

Special Collaborator

Retired Admin and Amateur Layabout Joined: May 13 2007 Location: Europe Status: Offline Points: 37575 |

Posted: January 13 2017 at 06:18 Posted: January 13 2017 at 06:18 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

But that isn't wholly true is it? The 15 seconds judgement is a consequence of 15 years experience and there is no escaping that.

I still say that isn't intuition but a conditioned response born from experience.

And I hate jam-bands and any improvised music that outstays its welcome (which is most of it) - and for that I'm not sorry. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

What?

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Davesax1965

Forum Senior Member

Joined: May 23 2013 Location: UK Status: Offline Points: 2839 |

Posted: January 13 2017 at 04:48 Posted: January 13 2017 at 04:48 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

It's partially intuitive. ;-)

"Intuition" based around a knowledge of the rules and genre, whether conscious or subconscious. The rules are there as a framework but intuition seems to be the higher function. That's the part which constitutes being a musician, your own personal take on the rules. This as a jazz saxer who improvises. Someone said that the difference between improvisation and composition is that, when composing a 15 second solo, you can call on years of experience. When improvising..... you have fifteen seconds. It's very difficult to describe what's going on in a musicians' head when soloing. You have point A, the start. You have point B, the end. There are bits in the middle. Now, you'll need a set of rules to get there, unless you're Ornette Coleman* but I think it's fair to say that there are two processes at work. There's a semi-automatic one where you're thinking "major triad, now, what note am I on ? OK, a descending major triad here..... " - you're referencing musical theory, subconsciously or not, but you're also working by intuition to the genre and reference to what other people are playing around you. Got to agree with you about the fact that there is no need to reference every note in a microtonal scale, unless you are some form of demented completist. ;-) I still hate gamelan music. Sorry, no. ;-) * joke

Edited by Davesax1965 - January 13 2017 at 04:50 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dean

Special Collaborator

Retired Admin and Amateur Layabout Joined: May 13 2007 Location: Europe Status: Offline Points: 37575 |

Posted: January 13 2017 at 03:20 Posted: January 13 2017 at 03:20 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

It isn't intuition as such, it's the application of learned experience. It appears intuitive because you don't have to think consciously about it but it's no different to tying shoe laces, driving a car or riding a bicycle - none of those actions are intuitive, they have to be taught but once mastered they become second-nature. If you have never learnt to play a musical instrument you cannot pick one up and intuitively play Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata, and the same is true of composition. You say that it isn't formulated but it is, you decide which key to begin in and which scale to use (and yes, I will say that both those are formula), you decide on the time signature (that is another formula) and you decide on the rhythm, phrasing, tempo and all the other elements that are necessary to play one note after the other (all of which are formulaic). Even the choice of which note to play next can be described as a formula, albeit an unspecified one because each successive note is not a wholly random choice - whether you call it instinctive or formulative, the next note you play will most likely have some harmonic relationship to the notes that preceded it and/or the underlying chord or bass line unless you deliberately want to create tension within that phrase before resolving that tension by returning back to harmonic relationship. You play a phrase and then repeat and/or progress it to produce a melody that can be considered to be formulated in some way or other (the most obvious is 12-bar blues, but even when Prog Rock dispenses with such simplistic music structure it is replaced by less obvious and more complex structure but it is still structured). As soon as you repeat a phrase you have defined a rule, it may be a rule that has never been used before but it is a rule just the same. The notes in that melody line will also determine the choice of chords and the chord progression that accompanies it (or vice versa depending on how you compose a tune), and once again that is not a wholly random choice. Music created in this way will sound (for want of a better word) composed, whereas music that has been created that doesn't fit those prescribed and well-chosen formula (for example by throwing sets of 8 or 12 sided dice, or throwing a xylophone down a flight of stairs) will not. Of course the taboo word here is "formulaic" because it implies some pretty negative connotations such as 'music by numbers' where the inference is that music composed to a formula lacks creativity and emotion, which is of course a complete nonsense, that would be like saying Shakespeare lacked creativity and emotion because he rigidly used Iambic Pentameter in his soliloquies and sonnets. {I don't believe for one minute that Bill sat there counting the syllables in each line, nor did he use 'intuition', he had learnt that each line in a verse fitted a ti-Dum ti-Dum ti-Dum ti-Dum ti-Dum rhythm with the stress on alternate 'beats' and he just ran with it without having to consciously think about it}. It is because composers adhere to these musical constraints that we get 'music'. By your own admission, music that does not is not music to your ears. Even atonal music sounds more (again for the want of a more appropriate word) composed when it follows some formulated process. Schoenberg devised some 'rules' for composing 12-tone music that was atonal (i.e., lacked a tonal-centre), these 'rules' ensured that no single note was more prominent than any other and so created Serialism. (Of course Riley then responded to that by devising a rule-set that contained a tonal centre and thus created Minimalism). The point being, while both these dispense with the traditional constraints of music theory, they merely replace them with new ones. With practice and experience these new rule-set also become 'intuitive' and second-nature. Just as composing music using Arabic maqam or Indian raga is second-nature to musicians who learnt their craft in those music systems.

Yup, more or less. Microtonal music has its own sets of rules to determine what happens next in any composition, if you want it to be harmonious and melodic then the choice of which note to play next is not wholly random. Now, with a 'musical ear' that is accustomed to harmonic music then those rules will not be any different to those used in the music that you are accustomed to hearing, a dissonant note is dissonant irrespective of your cultural background or musical education. As my previous posts show, composing in microtonal does not mean you have to use every note in that system, each microtonal system has numerous scales that are constructed from one or more notes from the total number in each octave. But you don't have to stick to using just one scale or just one key, you can even use ascending and descending scales just as you can in any other music system. What sounds melodic and harmonious is determined by which notes you play in any sequence regardless of which music system you are using.

No comment.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

What?

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Davesax1965

Forum Senior Member

Joined: May 23 2013 Location: UK Status: Offline Points: 2839 |

Posted: January 13 2017 at 01:15 Posted: January 13 2017 at 01:15 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Got to agree with the "cultural" influence, there.

My take on composition - well, my experience, anyway, is that it's intuitive, rather than formulated. I'm sure, as Dean says, that I of course have to rely on scales which have a mathematical structure. I don't do it consciously, and it's a very good point that I don't, of course. Some musicians do, each to their own. It's an excellent point that you don't have to "learn the rules first to know how to break them" and, to be honest, I'd never thought of that ! There has to be an element of cultural immersion in this otherwise it becomes an exercise in merely combining notes according to mathematical rules. As Dean says, "Experience is merely knowing the rules by heart regardless of how they were learnt." Jazz has rules and the rules vary, for, say, bebop as they are stylistically different from other forms of jazz. Referring back to the OP - "How do I compose microtonically ? " - the answer has to be "What are you trying to do or sound like ? ". You then have to refer to the rules pertinent to that style of music (if you want to fit in with a style) and immerse yourself in it. As Guilhermeafonso says there is always going to be music which doesn't suit our ears, and that's partially down to cultural heritage. Gamelan music might be structured, but I wouldn't know, as soon as I hear a snippet of it, I switch off (and switch over) after the first bar. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Post Reply

|

Page 123> |

| Forum Jump | Forum Permissions  You cannot post new topics in this forum You cannot reply to topics in this forum You cannot delete your posts in this forum You cannot edit your posts in this forum You cannot create polls in this forum You cannot vote in polls in this forum |