/PAlogo_v2.gif) |

|

Post Reply

|

Page <1 910111213 222> |

| Author | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

CinemaZebra

Forum Senior Member

Joined: March 13 2010 Location: Ancient Rome Status: Offline Points: 6795 |

Posted: July 08 2010 at 12:07 Posted: July 08 2010 at 12:07 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

That is the greatest love.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Man With Hat

Collaborator

Jazz-Rock/Fusion/Canterbury Team Joined: March 12 2005 Location: Neurotica Status: Offline Points: 166183 |

Posted: July 08 2010 at 15:43 Posted: July 08 2010 at 15:43 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I used to think it was possible. But then I became alive and saw the world for what it is. And now I think...I shouldn't have had the double order of tacos.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dig me...But don't...Bury me

I'm running still, I shall until, one day, I hope that I'll arrive Warning: Listening to jazz excessively can cause a laxative effect. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vompatti

Forum Senior Member

VIP Member Joined: October 22 2005 Location: elsewhere Status: Offline Points: 67471 |

Posted: July 08 2010 at 15:46 Posted: July 08 2010 at 15:46 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This is the last time I will kiss you.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Man With Hat

Collaborator

Jazz-Rock/Fusion/Canterbury Team Joined: March 12 2005 Location: Neurotica Status: Offline Points: 166183 |

Posted: July 08 2010 at 20:01 Posted: July 08 2010 at 20:01 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

You've always sung that line, even before the witches.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dig me...But don't...Bury me

I'm running still, I shall until, one day, I hope that I'll arrive Warning: Listening to jazz excessively can cause a laxative effect. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Atavachron

Special Collaborator

Honorary Collaborator Joined: September 30 2006 Location: Pearland Status: Offline Points: 65867 |

Posted: July 08 2010 at 22:44 Posted: July 08 2010 at 22:44 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Cameroon.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

JJLehto

Prog Reviewer

Joined: April 05 2006 Location: Tallahassee, FL Status: Offline Points: 34550 |

Posted: July 08 2010 at 23:18 Posted: July 08 2010 at 23:18 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

So, I've been thinking about if America should install a true Universal Health Care system...the US spends more on GDP (13%) than any other industrial country on healthcare, yet Americans use the system LESS than the average of those countries. Despite the price we pay, our health system was ranked 37th out of 191 overall. It has also been estimated that 18,000 unnecessary deaths happen per year, due to lack of health insurance and in 2007 over 60% of all bankruptcies were due to medical costs. This is very rare in most industrialized countries. Clearly the system is broken, and apparently lags behind most countries with universal healthcare.

Penis |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Atavachron

Special Collaborator

Honorary Collaborator Joined: September 30 2006 Location: Pearland Status: Offline Points: 65867 |

Posted: July 08 2010 at 23:20 Posted: July 08 2010 at 23:20 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

JJLehto

Prog Reviewer

Joined: April 05 2006 Location: Tallahassee, FL Status: Offline Points: 34550 |

Posted: July 08 2010 at 23:24 Posted: July 08 2010 at 23:24 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

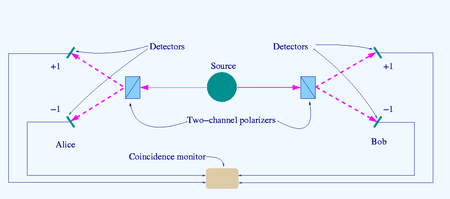

Bell’s theorem shows that there are limits that apply to local hidden-variable models of quantum systems, and that quantum mechanics (QM) predicts that these limits will be exceeded by measurements performed on entangled pairs of particles. This article discusses Bell’s theorem in the context of experiments that show that the predictions of quantum mechanics are consistent with the results of experiments, and inconsistent with local hidden variable models of quantum mechanics.

Illustration of Bell test for spin 1/2 particles. Source produces spin

singlet pair, one particle sent to Alice another to Bob. Each performs

one of the two spin measurements.

As in the situation explored in the Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen (EPR) paradox, Bell considered an experiment in which a source produces pairs of correlated particles. For example, a pair of particles with correlated spins is created; one particle is sent to Alice and the other to Bob. The experimental arrangement differs from the EPR arrangement in that the same type of measurement is performed on both particles of a pair. On each trial, each of the observers independently chooses between various detector settings and then performs an independent measurement on the particle arriving at their position. Hence, Bell’s theorem can be tested by coincidence measurements on pairs of entangled particles in which the correlation between two independently chosen measurements is determined. When Alice and Bob measure the spin† of entangled particles along the same axis (but in opposite directions), they get identical results 100% of the time. When Bob measures at orthogonal (right) angles to Alice’s measurements, his measurement matches hers 50% of the time. In terms of mathematics, the two measurements have a correlation of 1, or perfect correlation when read along the same axis (in opposite direction); when read at right angles, they have no correlation.

So far, (when the analyzers are aligned, orthogonal, or 45 degrees) the measurement results can be modeled by proposing physical attributes, referred to as local hidden variables, within each particle that determine the outcome of a measurement. If the analyzers are aligned, and the source only emits pairs of particles with identical properties then Alice and Bob’s measurements will match (+,+) and (-,-). Similarly, the results will be uncorrelated (+,-) (-,+) if their analyzers are aligned on orthogonal axes. Now, consider Alice or Bob set their analyzers so that their axes are at some arbitrary angle between 0 and 90 degrees. A quantum mechanical calculation of the degree to which Alice and Bob’s measurements will correlate results in a curve that varies as the cosine of twice the angle between the analyzers. That is, using entangled particles, there is a cosine curve from correlated (at zero degrees) and uncorrelated at 90 degrees. In contrast, Bell’s theorem places a straight-line limit on the curve that any local hidden variable model (involving identical particles) can follow from correlated to uncorrelated. The QM prediction for entangled particles breaks this limit. For example, when the relative analyzer alignment is 22.5 degrees QM gives 0.71 correlation whereas the straight-line limit (implied by Bell’s theorem) is 0.5. From this, one may conclude that the outcome of quantum measurements on entangled particles cannot be replicated by a model that employs identical particles that have hidden attributes/properties which locally determine the outcome of measurements. One possible way for a hidden variable system to break the limit imposed by Bell’s theorem, is to suppose that some non-local process or communication acts to increase the degree of correlation above the limits imposed by Bell’s theorem. To test this possibility, the analyzer angles are set at arbitrary angles before measuring the particles, even after the particles leave the source. In this case, this supposed non-local interaction or communication would have to occur instantaneously (i.e. travelling faster than light) in order to reproduce the behavior observed in quantum systems. Note that this does not necessarily mean that QM itself involves non-local or instantaneous communication, it just means that hidden variable accounts of QM would require these, or similar, drastic elements to be viable. Multiple researchers have performed equivalent experiments using different methods. It appears [1] that most of these experiments refute local-hidden-variable theories and support the notion that QM involves some degree of nonlocality. Not everyone agrees with these findings.[2] There have been two loopholes found in the earlier of these experiments, the detection loophole[1] and the communication loophole[1] with associated experiments to close these loopholes. After all current experimentation it seems these experiments support quantum mechanical non-locality [1] or disprove the ‘no enhancement’ assumption (below). Bell inequalities concern measurements made by observers on pairs of particles that have interacted and then separated. According to quantum mechanics they are entangled while local realism limits the correlation of subsequent measurements of the particles. Different authors subsequently derived inequalities similar to Bell´s original inequality, collectively termed Bell inequalities. All Bell inequalities describe experiments in which the predicted result assuming entanglement differs from that following from local realism. The inequalities assume that each quantum-level object has a well defined state that accounts for all its measurable properties and that distant objects do not exchange information faster than the speed of light. These well defined states are often called hidden variables, the properties that Einstein posited when he stated his famous objection to quantum mechanics: "God does not play dice." Bell showed that under quantum mechanics, which lacks local hidden variables, the inequalities may be violated. Instead, properties of a particle are not clear to verify in quantum mechanics but may be correlated with those of another particle due to quantum entanglement, allowing their state to be well defined only after a measurement is made on either particle. That restriction agrees with the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, a fundamental and inescapable concept in quantum mechanics. In Bell's work:

In probability theory, repeated measurements of system properties can be regarded as repeated sampling of random variables. In Bell's experiment, Alice can choose a detector setting to measure either A(a) or A(a') and Bob can choose a detector setting to measure either B(b) or B(b'). Measurements of Alice and Bob may be somehow correlated with each other, but the Bell inequalities say that if the correlation stems from local random variables, there is a limit to the amount of correlation one might expect to see. [edit] Original Bell's inequalityThe original inequality that Bell derived was:[3] where C is the "correlation" of the particle pairs and a, b and c settings of the apparatus. This inequality is not used in practice. For one thing, it is true only for genuinely "two-outcome" systems, not for the "three-outcome" ones (with possible outcomes of zero as well as +1 and −1) encountered in real experiments. For another, it applies only to a very restricted set of hidden variable theories, namely those for which the outcomes on both sides of the experiment are always exactly anticorrelated when the analysers are parallel, in agreement with the quantum mechanical prediction. There is a simple limit of Bell's inequality which has the virtue of being completely intuitive. If the result of three different statistical coin-flips A, B, and C have the property that:

then A and C are the same at least 98% of the time. The number of mismatches between A and B (1/100) plus the number of mismatches between B and C (1/100) are together the maximum possible number of mismatches between A and C. In quantum mechanics, by letting A, B, and C be the values of the

spin of two entangled particles measured relative to some axis at 0

degrees, θ degrees, and 2θ degrees respectively, the overlap of the wavefunction between the different angles is proportional to Imagine that two entangled particles in a spin singlet are shot out to two distant locations, and the spins of both are measured in the direction A. The spins are 100% correlated (actually, anti-correlated but for this argument that is equivalent). The same is true if both spins are measured in directions B or C. It is safe to conclude that any hidden variables which determine the A,B, and C measurements in the two particles are 100% correlated and can be used interchangeably. If A is measured on one particle and B on the other, the correlation between them is 99%. If B is measured on one and C on the other, the correlation is 99%. This allows us to conclude that the hidden variables determining A and B are 99% correlated and B and C are 99% correlated. But if A is measured in one particle and C in the other, the results are only 96% correlated, which is a contradiction. The intuitive formulation is due to David Mermin, while the small-angle limit is emphasized in Bell's original article. [edit] CHSH inequalityMain article: CHSH inequality

In addition to Bell's original inequality,[3] the form given by John Clauser, Michael Horne, Abner Shimony and R. A. Holt,[8] (the CHSH form) is especially important[8], as it gives classical limits to the expected correlation for the above experiment conducted by Alice and Bob: where C denotes correlation. Correlation of observables X, Y is defined as This is a non-normalized form of the correlation coefficient considered in statistics (see Quantum correlation). In order to formulate Bell's theorem, we formalize local realism as follows:

Implicit in assumption 1) above, the hidden parameter space Λ has a probability measure ρ and the expectation of a random variable X on Λ with respect to ρ is written where for accessibility of notation we assume that the probability measure has a density. Bell's inequality. The CHSH inequality (1) holds under the hidden variables assumptions above. For simplicity, let us first assume the observed values are +1 or −1; we remove this assumption in Remark 1 below. Let is 0. Thus and therefore Remark 1. The correlation inequality (1) still holds if the variables A(a,λ), B(b,λ) are allowed to take on any real values between −1 and +1. Indeed, the relevant idea is that each summand in the above average is bounded above by 2. This is easily seen to be true in the more general case: To justify the upper bound 2 asserted in the last inequality, without loss of generality, we can assume that In that case Remark 2. Though the important component of the hidden parameter λ in Bell's original proof is associated with the source and is shared by Alice and Bob, there may be others that are associated with the separate detectors, these others being independent. This argument was used by Bell in 1971, and again by Clauser and Horne in 1974,[9] to justify a generalisation of the theorem forced on them by the real experiments, in which detectors were never 100% efficient. The derivations were given in terms of the averages of the outcomes over the local detector variables. The formalisation of local realism was thus effectively changed, replacing A and B by averages and retaining the symbol λ but with a slightly different meaning. It was henceforth restricted (in most theoretical work) to mean only those components that were associated with the source. However, with the extension proved in Remark 1, CHSH inequality still holds even if the instruments themselves contain hidden variables. In that case, averaging over the instrument hidden variables gives new variables: on Λ which still have values in the range [−1, +1] to which we can apply the previous result. [edit] Bell inequalities are violated by quantum mechanical predictionsIn the usual quantum mechanical formalism, the observables X and Y are represented as self-adjoint operators on a Hilbert space. To compute the correlation, assume that X and Y are represented by matrices in a finite dimensional space and that X and Y commute; this special case suffices for our purposes below. The von Neumann measurement postulate states: a series of measurements of an observable X on a series of identical systems in state φ produces a distribution of real values. By the assumption that observables are finite matrices, this distribution is discrete. The probability of observing λ is non-zero if and only if λ is an eigenvalue of the matrix X and moreover the probability is where EX (λ) is the projector corresponding to the eigenvalue λ. The system state immediately after the measurement is From this, we can show that the correlation of commuting observables X and Y in a pure state ψ is We apply this fact in the context of the EPR paradox. The measurements performed by Alice and Bob are spin measurements on electrons. Alice can choose between two detector settings labelled a and a′; these settings correspond to measurement of spin along the z or the x axis. Bob can choose between two detector settings labelled b and b′; these correspond to measurement of spin along the z′ or x′ axis, where the x′ – z′ coordinate system is rotated 135° relative to the x – z coordinate system. The spin observables are represented by the 2 × 2 self-adjoint matrices: These are the Pauli spin matrices normalized so that the corresponding eigenvalues are +1, −1. As is customary, we denote the eigenvectors of Sx by Let φ be the spin singlet state for a pair of electrons discussed in the EPR paradox. This is a specially constructed state described by the following vector in the tensor product Now let us apply the CHSH formalism to the measurements that can be performed by Alice and Bob. The operators B(b'), B(b) correspond to Bob's spin measurements along x′ and z′. Note that the A operators commute with the B operators, so we can apply our calculation for the correlation. In this case, we can show that the CHSH inequality fails. In fact, a straightforward calculation shows that and so that Bell's Theorem: If the quantum mechanical formalism is correct, then

the system consisting of a pair of entangled electrons cannot satisfy

the principle of local realism. Note that [edit] Practical experiments testing Bell's theoremMain article: Bell test experiments

Scheme of a "two-channel" Bell test

The source S produces pairs of "photons", sent in opposite directions. Each photon encounters a two-channel polariser whose orientation (a or b) can be set by the experimenter. Emerging signals from each channel are detected and coincidences of four types (++, −−, +− and −+) counted by the coincidence monitor. Experimental tests can determine whether the Bell inequalities required by local realism hold up to the empirical evidence. Bell's inequalities are tested by "coincidence counts" from a Bell test experiment such as the optical one shown in the diagram. Pairs of particles are emitted as a result of a quantum process, analysed with respect to some key property such as polarisation direction, then detected. The setting (orientations) of the analysers are selected by the experimenter. Bell test experiments to date overwhelmingly violate Bell's inequality. Indeed, a table of Bell test experiments performed prior to 1986 is given in 4.5 of Redhead, 1987.[10] Of the thirteen experiments listed, only two reached results contradictory to quantum mechanics; moreover, according to the same source, when the experiments were repeated, "the discrepancies with QM could not be reproduced". Nevertheless, the issue is not conclusively settled. According to Shimony's 2004 Stanford Encyclopedia overview article:[1]

To explore the 'detection loophole', one must distinguish the classes of homogeneous and inhomogeneous Bell inequality. The standard assumption in Quantum Optics is that "all photons of given frequency, direction and polarization are identical" so that photodetectors treat all incident photons on an equal basis. Such a fair sampling assumption generally goes unacknowledged, yet it effectively limits the range of local theories to those which conceive of the light field as corpuscular. The assumption excludes a large family of local realist theories, in particular, Max Planck's description. We must remember the cautionary words of Albert Einstein[11] shortly before he died: "Nowadays every Tom, Dick and Harry ('jeder Kerl' in German original) thinks he knows what a photon is, but he is mistaken". Objective physical properties for Bell’s analysis (local realist theories) include the wave amplitude of a light signal. Those who maintain the concept of duality, or simply of light being a wave, recognize the possibility or actuality that the emitted atomic light signals have a range of amplitudes and, furthermore, that the amplitudes are modified when the signal passes through analyzing devices such as polarizers and beam splitters. It follows that not all signals have the same detection probability[12]. [edit] Two classes of Bell inequalitiesThe fair sampling problem was faced openly in the 1970s. In early designs of their 1973 experiment, Freedman and Clauser[13] used fair sampling in the form of the Clauser-Horne-Shimony-Holt (CHSH[8]) hypothesis. However, shortly afterwards Clauser and Horne[9] made the important distinction between inhomogeneous (IBI) and homogeneous (HBI) Bell inequalities. Testing an IBI requires that we compare certain coincidence rates in two separated detectors with the singles rates of the two detectors. Nobody needed to perform the experiment, because singles rates with all detectors in the 1970s were at least ten times all the coincidence rates. So, taking into account this low detector efficiency, the QM prediction actually satisfied the IBI. To arrive at an experimental design in which the QM prediction violates IBI we require detectors whose efficiency exceeds 82% for singlet states, but have very low dark rate and short dead and resolving times. This is well above the 30% achievable[14] so Shimony’s optimism in the Stanford Encyclopedia, quoted in the preceding section, appears over-stated. [edit] Practical challengesMain article: Loopholes in Bell test experiments

Because detectors don't detect a large fraction of all photons, Clauser and Horne[9] recognized that testing Bell's inequality requires some extra assumptions. They introduced the No Enhancement Hypothesis (NEH):

Given this assumption, there is a Bell inequality between the coincidence rates with polarizers and coincidence rates without polarizers. The experiment was performed by Freedman and Clauser[13], who found that the Bell's inequality was violated. So the no-enhancement hypothesis cannot be true in a local hidden variables model. The Freedman-Clauser experiment reveals that local hidden variables imply the new phenomenon of signal enhancement:

This is perhaps not surprising, as it is known that adding noise to data can, in the presence of a threshold, help reveal hidden signals (this property is known as stochastic resonance[15]). One cannot conclude that this is the only local-realist alternative to Quantum Optics, but it does show that the word loophole is biased. Moreover, the analysis leads us to recognize that the Bell-inequality experiments, rather than showing a breakdown of realism or locality, are capable of revealing important new phenomena. [edit] Theoretical challengesMost advocates of the hidden variables idea believe that experiments have ruled out local hidden variables. They are ready to give up locality, explaining the violation of Bell's inequality by means of a "non-local" hidden variable theory, in which the particles exchange information about their states. This is the basis of the Bohm interpretation of quantum mechanics, which requires that all particles in the universe be able to instantaneously exchange information with all others. A recent experiment ruled out a large class of non-Bohmian "non-local" hidden variable theories.[16] If the hidden variables can communicate with each other faster than light, Bell's inequality can easily be violated. Once one particle is measured, it can communicate the necessary correlations to the other particle. Since in relativity the notion of simultaneity is not absolute, this is unattractive. One idea is to replace instantaneous communication with a process which travels backwards in time along the past Light cone. This is the idea behind a transactional interpretation of quantum mechanics, which interprets the statistical emergence of a quantum history as a gradual coming to agreement between histories that go both forward and backward in time[17]. A few advocates of deterministic models have not given up on local hidden variables. E.g., Gerard 't Hooft has argued that the superdeterminism loophole cannot be dismissed[18]. The quantum mechanical wavefunction can also provide a local realistic description, if the wavefunction values are interpreted as the fundamental quantities that describe reality. Such an approach is called a many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. In this view, two distant observers both split into superpositions when measuring a spin. The Bell inequality violations are no longer counterintuitive, because it is not clear which copy of the observer B observer A will see when going to compare notes. If reality includes all the different outcomes, locality in physical space (not outcome space) places no restrictions on how the split observers can meet up. This implies that there is a subtle assumption in the argument that realism is incompatible with quantum mechanics and locality. The assumption, in its weakest form, is called counterfactual definiteness. This states that if the results of an experiment are always observed to be definite, there is a quantity which determines what the outcome would have been even if you don't do the experiment. Many worlds interpretations are not only counterfactually indefinite, they are factually indefinite. The results of all experiments, even ones that have been performed, are not uniquely determined. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

CinemaZebra

Forum Senior Member

Joined: March 13 2010 Location: Ancient Rome Status: Offline Points: 6795 |

Posted: July 08 2010 at 23:30 Posted: July 08 2010 at 23:30 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sexy.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

DisgruntledPorcupine

Forum Senior Member

Joined: January 16 2010 Location: Thunder Bay CAN Status: Offline Points: 4395 |

Posted: July 08 2010 at 23:45 Posted: July 08 2010 at 23:45 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

*asplodes*

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

CinemaZebra

Forum Senior Member

Joined: March 13 2010 Location: Ancient Rome Status: Offline Points: 6795 |

Posted: July 09 2010 at 00:32 Posted: July 09 2010 at 00:32 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Post after me if you think the actress Michelle Johnson is the hottest woman on earth.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A Person

Forum Senior Member

Joined: November 10 2008 Location: __ Status: Offline Points: 65760 |

Posted: July 09 2010 at 00:42 Posted: July 09 2010 at 00:42 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I forgot how to play this game.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Atavachron

Special Collaborator

Honorary Collaborator Joined: September 30 2006 Location: Pearland Status: Offline Points: 65867 |

Posted: July 09 2010 at 01:18 Posted: July 09 2010 at 01:18 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mom?

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

AtomicCrimsonRush

Special Collaborator

Honorary Collaborator Joined: July 02 2008 Location: Australia Status: Offline Points: 14258 |

Posted: July 09 2010 at 10:53 Posted: July 09 2010 at 10:53 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spongebob Squarepants is singing to PATRICK

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Atavachron

Special Collaborator

Honorary Collaborator Joined: September 30 2006 Location: Pearland Status: Offline Points: 65867 |

Posted: July 09 2010 at 20:13 Posted: July 09 2010 at 20:13 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Great Moments in Opera #23 - Mimi commits suicide.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Man With Hat

Collaborator

Jazz-Rock/Fusion/Canterbury Team Joined: March 12 2005 Location: Neurotica Status: Offline Points: 166183 |

Posted: July 09 2010 at 20:22 Posted: July 09 2010 at 20:22 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I often express my feelings in coughing up various foodstuffs I refuse to eat.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dig me...But don't...Bury me

I'm running still, I shall until, one day, I hope that I'll arrive Warning: Listening to jazz excessively can cause a laxative effect. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Atavachron

Special Collaborator

Honorary Collaborator Joined: September 30 2006 Location: Pearland Status: Offline Points: 65867 |

Posted: July 09 2010 at 20:24 Posted: July 09 2010 at 20:24 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Cleaning public bathrooms is not as rewarding as you might think.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

CinemaZebra

Forum Senior Member

Joined: March 13 2010 Location: Ancient Rome Status: Offline Points: 6795 |

Posted: July 09 2010 at 21:07 Posted: July 09 2010 at 21:07 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Edited by CinemaZebra - July 09 2010 at 21:08 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Atavachron

Special Collaborator

Honorary Collaborator Joined: September 30 2006 Location: Pearland Status: Offline Points: 65867 |

Posted: July 09 2010 at 21:42 Posted: July 09 2010 at 21:42 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Is ice.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Man With Hat

Collaborator

Jazz-Rock/Fusion/Canterbury Team Joined: March 12 2005 Location: Neurotica Status: Offline Points: 166183 |

Posted: July 09 2010 at 22:03 Posted: July 09 2010 at 22:03 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Cod cookies sound delicious. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dig me...But don't...Bury me

I'm running still, I shall until, one day, I hope that I'll arrive Warning: Listening to jazz excessively can cause a laxative effect. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Post Reply

|

Page <1 910111213 222> |

| Forum Jump | Forum Permissions  You cannot post new topics in this forum You cannot reply to topics in this forum You cannot delete your posts in this forum You cannot edit your posts in this forum You cannot create polls in this forum You cannot vote in polls in this forum |